Worship Movements 3/5: New Tunes, New Spirit

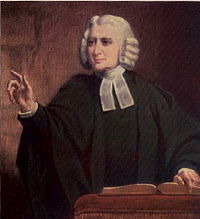

A radical thing happened a while ago. Folks started singing words of faith to tunes sounding much like the secular tunes of the day. And I’m not talking about the contemporary worship movement. I’m talking about the Wesleys, the founders of the Methodist movement. John and Charles, contrary to popular belief, did not use bar tunes, but rather tunes written by theater troubadours. In 1746, the wife of the proprietor of Covent Garden Theater in London’s theater district was converted to Methodism, and she put Charles in touch with the most popular theater composers of the day. They set the Wesley’s texts to their tunes and a new genre of congregational singing was born.

The book English Hymn: Its Development and Use in Worship describes the new hymn-singing experience: “The new hymns both fed and expressed the new feelings; and the thrill of spiritual passion leaped from heart to heart of the great concourse singing together, ”˜Blow ye the trumpet, blow’ and ”˜O for a thousand tongues to sing.’”

So as we look at the worship movements of the 20th century, the “radical” shift in music practices of the contemporary movement don’t seem so new. The question of how to stir the passion of the people has always been in place as each generation pushes up against the last one.

But here’s the thing…I consult with so many mainline congregations whose “contemporary” services have lost their vigor, or their passion. Praise bands bemoan the fact that people just stand there with their hands in their pockets and watch most of the time. “Why aren’t they singing?” they ask me.

As we read on in the book of the English Hymn, we hear something that seems quite familiar: “As time went on…exuberance naturally lessened, and were followed by the creeping in of formality. . . . A new danger arose with the formation of a body of “Singers” to lead the worship of the chapels.” The text goes on to describe that before the formation of choirs, the preacher or other leader would line out the hymns until they got familiar enough to be sung “impulsively” by the whole body. In other words, somebody was leading the congregation actively in their participation. As the choir and the organ eventually developed, the people were left behind as tunes became more “florid,” apparently something Charles Wesley hated.

So, here is what I tell praise bands that bemoan the lack of singing in the congregation:

”¢ They aren’t singing because you aren’t actively teaching and leading the songs.

”¢ They aren’t singing because the songs you are singing were written by and for a band and professional singers and the melody lines aren’t all suitable (i.e. doable) for congregational participation–they are “florid” tunes.

So, if your “contemporary” (1980’s baby-boomer-style) worship is lagging, there are several things to do to enrich it. I’ll just speak to music this week but will write more about how other art forms can help out as well next week.

As you practice the music with your band, spend just as time on planning how you will teach and lead the congregation as you do on rehearsing the musical elements. Perhaps you need to sing the first verse, inviting the congregation to listen, and then repeat that same verse, inviting them to sing with you. Perhaps you need to invite them to listen to the verses and join you in singing the refrains (which are often easier melody lines than the verses).

Spend time “choreographing” how you will invite the congregation to bodily-kinesthetic participation. Just saying to a congregation, “clap your hands!” will not automatically garner the results you hoped for. You have to model the energy you want to receive. If you are a main worship leader but your hands are busy playing the guitar or keyboards, other vocalists will need to model bodily participation. Congregations won’t just do it on their own. Be specific about times when they will clap, because usually clapping through a whole song is not actually sustainable physically. Bringing them in for clapping on the refrain each time is a way to bump up the energy.

Be mindful that mainline denominations don’t have the same DNA as the evangelical congregations that most contemporary Christian music is born within. The strategy of singing a chorus many, many times is a way of whipping up the ecstasy or winding deeper and deeper. This style may feels quite like “home” for evangelical expressions of worship, but not for many mainline congregations. The 7th time you sing a refrain might be infinitely more interesting to the musicians than the congregation, who are way “over it” by now. You don’t have to sing as many repeats as the recording; gauge the length by paying attention to the attention and energy-span of your congregation.

Finally, here’s the hard pill to swallow for baby-boomers: The 1980’s-90’s contemporary model is not the latest thing anymore. The song “Sanctuary” is over 30 years old! Emerging generations are utilizing many genres of music in their worship besides CCM: world music, reggae, jazz, chant, old and new hymnody, old hymns to new arrangements, secular songs, bluegrass and “newgrass.” Join the crowd that says using only one genre of music is not only passé, it’s spiritually stifling. Mix it up, just like the Wesleys! You might just find you have a revival movement on your hands.

For more ideas about celebrating the diversity in your worship, join us in the Worship Design Studio and be sure to sign up for our mailing list at marciamcfee.com!