"Symbols: Drawing Meaning from the Ordinary Stuff of Life"

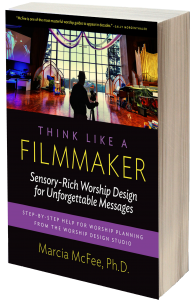

This is an excerpt from Dr. Marcia McFee’s new book [Think Like a Filmmaker © Marcia McFee, 2016]. Find out more HERE.

The tangible symbols in our midst are a hot point for a lot of churches. Actually, I should say the “objects” are a hot point because problems occur when objects get detached from their symbolic meaning. We hold beliefs about what should or shouldn’t be on the table, what candlesticks (given “in memory of”) we must use forever-more, and why it would be absolute sacrilege to get rid of that modesty rail in the chancel that hides the choir members, who wear long robes anyway! Actually, it is no wonder we have problems over our worship “stuff” considering how attached we get to a lot of tangible items in our lives. And usually this attachment isn’t about the actual objects at all. Anger over changing the candlesticks isn’t about the candlesticks, it is usually about, for instance, the grief that most of the congregation no longer remembers “Aunt Betty,” stalwart saint of the church, whose name appears on the plaque. Losing the candlesticks means losing an era. Our problem lies in that we’ve forgotten to associate the religious meaning and the spiritual depth that visual art forms offer. And when symbols lose their deeper meaning, we will attach any meaning to them. The candlesticks come to represent our attachment to Aunt Betty and a bygone era, not to the Light of Christ that shines in our midst.

The tangible symbols in our midst are a hot point for a lot of churches. Actually, I should say the “objects” are a hot point because problems occur when objects get detached from their symbolic meaning. We hold beliefs about what should or shouldn’t be on the table, what candlesticks (given “in memory of”) we must use forever-more, and why it would be absolute sacrilege to get rid of that modesty rail in the chancel that hides the choir members, who wear long robes anyway! Actually, it is no wonder we have problems over our worship “stuff” considering how attached we get to a lot of tangible items in our lives. And usually this attachment isn’t about the actual objects at all. Anger over changing the candlesticks isn’t about the candlesticks, it is usually about, for instance, the grief that most of the congregation no longer remembers “Aunt Betty,” stalwart saint of the church, whose name appears on the plaque. Losing the candlesticks means losing an era. Our problem lies in that we’ve forgotten to associate the religious meaning and the spiritual depth that visual art forms offer. And when symbols lose their deeper meaning, we will attach any meaning to them. The candlesticks come to represent our attachment to Aunt Betty and a bygone era, not to the Light of Christ that shines in our midst.

Reclaiming the power of symbol is one way visual artists can help the whole congregation. We can educate about the deeper meaning of our traditional and permanent symbols in the space (including “furniture” like the font, pulpit, and table) as well as introduce them to ordinary objects from everyday life that can hold symbolic meaning for a worship series. Let’s go a little deeper into how symbols function.

Symbol (from symbolein, meaning “to throw together”) acts to fit together the element serving as symbol and the context in which it resides. An element is not a symbol without context. It is this fitting together that makes it symbol (or in the linguistic term, metaphor (Paul Ricouer, “Metaphor and Philosophical Discourse” in The Rule of Metaphor: Multi-disciplinary Studies of the Creation of Meaning in Language, pp. 257-313). For instance, water used in the rite of baptism is the element of water “thrown together” with the context in which the water resides. In our everyday lives, we know water as sustenance for life as it quenches our thirst and washes us clean. We can associate all the bodies of water we love, such as oceans, lakes, and rivers. That is thrown together with the faith narrative when we bring water into the context of worship””the water of liberation through the Red Sea; the water of birth, death, and resurrection; the water of the baptism of Jesus; and the baptismal water which connects the community of saints of the church, living and past. It does what symbols do””it points beyond itself to something much more.

Secondly, symbol functions to “crystallize.” It makes the abstract “most real” by making it more tangible. Ritual scholar Mary Collins likens symbols to electric transformers (Mary Collins, Contemplative Participation, p. 40). Huge amounts of energy come over the wires that would blow up our houses if we used the raw current. But when the energy goes through a transformer, it becomes usable. The water crystallizes and communicates such a mysterious concept as renewal, forgiveness, and the power of the Holy Spirit””concepts that might be difficult for us to grasp were it not for our understanding of how water refreshes, washes clean, and gives us life. Making big concepts concrete is a huge gift to the congregation as we grapple to understand our faith.

Let me use another example. When I was about to turn 40 years old, I wanted to do something I thought I would never do in my entire lifetime as a kind of rite of passage. There were two things I thought I would never do: skydive, and get a tattoo. I was not about to jump out of an airplane. So I decided to get a tattoo. I actually love watching TV shows about tattoo artists, because I love hearing the stories about why people are getting their particular tattoos. There is always a story behind it, and the artwork serves as a symbol of that story. I decided to get the words “peace” and “passion” in Chinese calligraphy. I use those words in closing all my e-mail communication and when I give a benediction in worship. They have come to be a symbol of my relationships and ministry. At the time, my father had also just remarried a woman with Chinese heritage, so I asked her to write out the words. Thus the tattoo also became a symbol of that new relationship. Add to that its timing on my 40th birthday, and that tattoo is now full of much more meaning than just ink in my leg. There are multiple meanings to good symbols. The term we use to describe this is that symbols are “multivalent.” They will mean different things to different people based on our experience.

**Questions to Ponder:

Which symbols from our Christian faith narrative are particularly meaningful to us, from an individual, personal perspective? Why?

Which symbols from our Christian heritage are not so meaningful for us, personally? It’s OK not to find meaning in every aspect of every ritual””in fact, it’s good to know what our symbolic “strengths and weaknesses are”””so long as we are sure to honor the value that others see.**

Stay tuned for next week’s post, in which we’ll be discussing another one of the five major arts areas: the verbal arts. If you’d like to learn more about Think Like a Filmmaker, visit the book's website HERE.