"Musical Transitions"

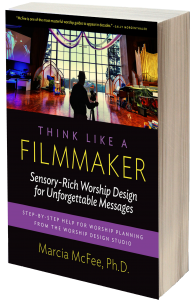

This is an excerpt from Dr. Marcia McFee’s new book [Think Like a Filmmaker © Marcia McFee, 2016]. Find out more HERE.

Imagine this moment: The bulletin says it is time for the anthem. The choir director stands and moves the music stand into place in front of the choir. Then comes the motion for the choir to stand. Then everyone gets their music open to the right place while the choir director waits. When it seems all are settled, the choir director looks to the accompanist and the accompanist nods to indicate readiness. The choir director looks back to the choir to make sure all eyes are focused, that all members will be ready for the downbeat. Finally, the anthem’s introduction begins. Certainly a “moment” has been created, but for what purpose? As all of these machinations have been occurring, the congregation has sat watching it, pulled out of the story and into an approximation of what they might experience at a concert hall.

Imagine this moment: The bulletin says it is time for the anthem. The choir director stands and moves the music stand into place in front of the choir. Then comes the motion for the choir to stand. Then everyone gets their music open to the right place while the choir director waits. When it seems all are settled, the choir director looks to the accompanist and the accompanist nods to indicate readiness. The choir director looks back to the choir to make sure all eyes are focused, that all members will be ready for the downbeat. Finally, the anthem’s introduction begins. Certainly a “moment” has been created, but for what purpose? As all of these machinations have been occurring, the congregation has sat watching it, pulled out of the story and into an approximation of what they might experience at a concert hall.

Imagine another moment: A sermon in the midst of a worship series called “Moving Out of Scare City” that focuses on the Gospel good news in the midst of a culture of fear has just finished with the preacher almost whispering an invitation, “Be still, quiet your heart, and know that God is near.” The worship guide indicates a time of silence. The lights are dimmed in the sanctuary. Out of the hushed silence, an unaccompanied voice eventually sings from among the still-seated choir. “I will come to you in the silence…” The voice pauses to breathe, then stands slowly with the next line. “I will lift you from all your fear…” A few more voices from the choir join as they slowly stand… “You will hear my voice, I claim you as my choice, be still and know I am here.” The piano sneaks in softly. The choir director moves slowly into place as the rest of the choir slowly stands. The lights in the choir loft have slowly come up, mimicking the timing of the choir slowly standing. The choir begins to sing the refrain, “Do not be afraid, I am with you…” and the good news of the sermon begins to be embodied in the music, having flowed seamlessly without breaking the mood of the moment for preparations (lyrics by David Haas excerpted from “You Are Mine” in The Faith We Sing, 2000).

In a concert setting, we present a piece of music for the sake of maximum appreciation of that piece of music. In that setting, the audience expects the routine of musicians readying themselves as we sit quietly waiting for the first strains of the composition. In worship, as in film and musical theater, the music is there to progress the message of the story. Anything that pulls us out of the story has little place in the progression of events. “Hollywood technique, no matter how flamboyant, at its best prides itself on being invisible, on serving the story. ”˜If you’re admiring the work,’ the saying goes, ”˜it’s not working.’ You been pulled out of the picture” (Jon Boorstin, Making Movies Work, p. 45). While not every anthem has to be as dramatically staged as the example above, planning the flow into any element of worship must be approached with intention.

I’ve been called “the flow queen” (hopefully lovingly!) by many worship artists who have worked under my direction. This is because I am adamant about rehearsing transitions. I had a dance mentor once tell me, “dancers who can do a triple pirouette are a dime-a-dozen. What distinguishes a technician from an artist is knowing how to get out of that triple pirouette and into the next step with ease and beauty.” I know that worship in which transitions have been intentionally attended to is worship that flows. And worship that flows is worship that keeps us “in the story.” Music is one of the key components in smoothing transitions from one element in the order of worship to another. Let’s hear what filmmakers know about the role of the music in the editing process:

"Music can tie together a visual medium that is, by its very nature, continually in danger of falling apart. A film editor is probably most conscious of this particular attribute of music in films. In a montage, particularly, music can serve an almost indispensable function: it can hold the montage together with some sort of unifying musical idea. Without music the montage can, in some instances, become merely chaotic. Music can also develop this sense of continuity on the level of the film as a whole." (Roy A. Prendergast, “The Aesthetics of Film Music” in A Neglected Art: A Critical Study of Music in Film, pp. 213-245)

Worship can often feel like a “montage” of disjointed pieces. A rousing hymn finishes and you can feel the energy crackling in the room. Because the reader who is leading the Call to Worship forgot when to move into place, we all stand in the silence watching them walk up the chancel stairs to the lectern. The energy we’ve just created plummets as we suffer through the awkward pause. Or the children are invited forward for a segment with the pastor, and the extended time it takes because a couple of them are “wandering” on their way forward creates a vacuum of energy that has to ramp up again when all are settled. In both of these examples, some impromptu “traveling music” from an instrumentalist could have alleviated the pregnant and unintentional pause in the energetic movement of worship. Empowering musicians to be alert to the possibility (the probability) that this will happen on occasion can keep them on-the-ready to provide important support in the moment. Actually planning for musical transitions when you know you will need one (as in the case of children moving up and back) is also a good idea. Musical transitions can also be planned for in rehearsal when you see the need to move the energy from one dynamic to another.

**Questions to Ponder:

Have we ever experienced a moment in worship where dead silence jarred us from the experience?

Think about the places where transitions currently occur in your order of worship. How would the addition of some simple instrumental music in the background segue us into the next action?**

Stay tuned for my next post, in which we’ll be discussing another one of the five major arts areas: the media arts. If you’d like to learn more about Think Like a Filmmaker, visit the book's website HERE.