Joanna M. Adams: White Southerners, our souls are at stake. We must speak up now

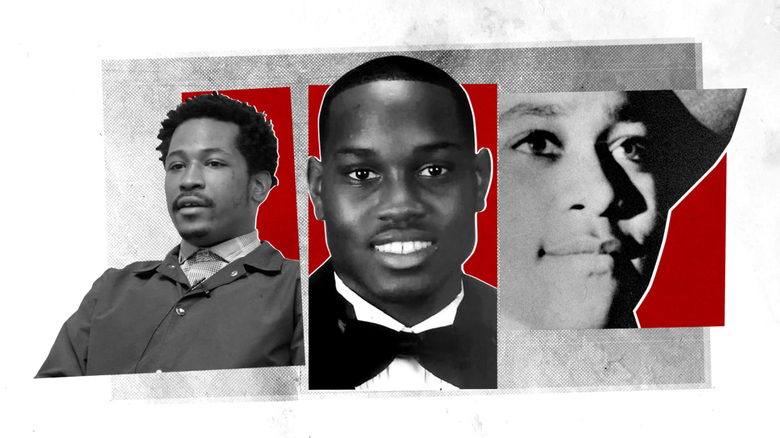

Two bullets in the back of Rayshard Brooks. His crime? Falling asleep in a long Wendy's pickup line in Atlanta. Drunk. Offered to walk to his sister's nearby home. No. Officers talked to him for half an hour. Then went after him with their guns when he tried to escape, waving a Taser he had grabbed from one of the officers.

"Got him," one of them said as Rayshard fell to the asphalt. Sounded like hunters hunkered in a duck blind whose marksmanship had resulted in a kill. "Got him."

Ahmaud Arbery shot down on a suburban street in Glynn County. His crime? Being Black in a place where the color of his skin turned out to be a capital offense. The three White men who had chased him for blocks stood over his body, allegedly using the n--- word, clearly satisfied with the success of their mission. They had gotten Arbery for sure.

I have lived in Atlanta -- where Brooks was killed -- for 58 years. These days, I spend a lot of time in southern Georgia, near the place where Arbery died. The Golden Isles, where red fish are there for the taking from the waters of the Satilla River -- Satilla Shores is the neighborhood where the shotgun blast ripped his body apart.

Southern is what I am through and through. I am also as White as a White person can be. When I traced my genealogy, I discovered that every single one of my ancestors many centuries back was from the British Isles, with a couple of Germans thrown in for diversity's sake. I am aware that all of us homo sapiens can trace our beginnings to Africa, but most White people couldn't care less.

As a child growing up in Mississippi in the 1950s, I thought nothing about race. I knew no Black people, other than the janitor at my school and our maid, Omera, whom I loved but whose last name I never knew. My parents probably didn't either. They paid her in cash -- I'm pretty sure it was not much. Occasionally, my mother did send her home with used tin cans full of bacon drippings.

One day, Omera told my mother that she and her family were moving to Detroit. It sounded like Mars to me. I cried. Omera and I hugged as we said goodbye. As we watched her walk to the bus stop down the street, Mother turned me around and said, "Jo, I know you love Omera, but I don't want you ever again to hug a 'Negra'. It's just not done."

This was Mississippi in the 1950s. My father worked for the Chamber of Commerce in our town, Meridian. The big event of the year, both for the Chamber and for the city, was the Calf Scramble Parade on a spring Saturday. The preceding Friday night, our high school stadium would be filled with people from all over the county who had come to watch young men wrestle calves to the ground on the football field and lasso them. The victors would take their newly subdued calves to raise them, though eventually the calves would become cows and sold to a slaughterhouse.

Come Saturday, the city was gathered on downtown sidewalks for the best parade of the year: Men wearing ten gallon hats and embroidered boots, riding on prancing stallions, bright red fire engines sounding their sirens, and the mayor sitting on the back seat of his convertible, his starched white shirt soaked with perspiration while he waved listlessly to the crowd.

Then came the floats, the skirts of which consisted of chicken wire, each little quadrangle of which was stuffed with white Kleenex bouquets, meant to look like carnations.

Lovely White girls sat on the floats, waving enthusiastically and smiling like Miss America. I wanted to be just like them. I was just a kid then, standing on the sidewalk with a couple of friends. We had ridden the bus downtown for a nickel. Ten or 11 years old, we were. Safe as could be. Besides, my father was in charge of the parade.

Then, this: A float from the Black grammar school in "colored town" came into view. I had never heard of that school and did not even know there was a Black grammar school.

But there was the float. Same chicken wire. Same Kleenex carnations. Riding on the float were three little girls looking like a million dollars in their ruffled dresses. The girls on the float were about my age, smiling with pride and delight.

All of a sudden, three White boys, much older than my friends and me, standing next to us in jeans, cowboy hats and boots, yelled out, "No n--- wanted here." One of them walked toward the float and spit on one of the girls. Another, then another did the same. And so it went.

You know how sometimes parades stop because of the horses up ahead slow down, or the clown works the crowd too long? The parade did not move.

Plenty of time for the all-White bystanders to speak up. No one did. Just silence. Did I speak up? I was nauseated, but I was also frightened. I was also a child, a child of the south. I was afraid, my tongue frozen in my mouth.

Those Black kids, my age and as unknown to me as they possibly could be in the segregated south.

My shame for the rest of my life.

In 2020, spit has turned into bullets. Back in my old southern days, there were plenty of bullets in Black people's back -- and in their fronts too. Plenty of Black women raped. Plenty of lynching. Emmett Till, a fourteen-year-old kid, was thrown into a river in Mississippi with a heavy industrial fan tied to his feet. They got him for sure. When a neighbor saw blood in the bed of his neighbor's truck and asked about it, the neighbor said, "We just killed a deer." He was one of the murderers.

White southerners, we must speak up now -- Black lives matter. Our souls are at stake, as is American society. Too many of us observe the parade of Black deaths and close our eyes to the scourge of white supremacy and say not a word. Neither do we do much of anything that matters or helps bring about change.

You and I can never know what it is like to be Black, but by God, we can do better than we have done for generations. Shame on us if we don't.

Originally posted on CNN.com. Reposted by permission of the author.